Speak Nearby, a collaborative exhibition by Ragnheiður Gestsdóttir, Theresa Himmer and Emily Weiner

November 1–December 6, 2015

Opening reception Sunday, November 1, 6:00–8:00 p.m.

Three is a Magic Number

Markús Þór Andrésson

Three is company and four is a crowd, as they say. With three variables you have a considerable choice of combinations, and by adding further sets of three the permutations increase exponentially. Equivocality prompts the rendezvous of the artists in the exhibition Speak Nearby, who, through their work, reveal a range of hidden and undisguised triadic elements. Ragnheiður Gestsdóttir, Theresa Himmer and Emily Weiner put the singularity of images and ideas to the test in the space that claims to offer all possibilities, which is art. Introducing distinct methods of appropriation, they playfully draw on established domains such as anthropology, history, physics, semiotics and philosophy. Before taking the artists’ individual contributions into further consideration, it might be useful to dwell on the general consensus that meaning is provisional and subject to many interpretations.

An artist who casts all truths into question—manifesting in her artwork limitless readings—must nevertheless do so within a set of finite frameworks. We are all working with the same set of tools, but within different temporal, cultural and political parameters. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that those frameworks are often notably limited to the number three. Being trichromatic, the human retina contains three kinds of color receptors that make up all possible formulas for the visible world. Three is furthermore the number of spatial dimensions that humans can perceive. The artist may attempt to suggest potentials over and above the realm of perception, clinging to string theory and beyond, but evidence indicates that there are limits to art as a language. Language itself, despite its seemingly infinite potential, has distinct limits. A dictionary is one kind—just take as an example the English term “three”, the Danish “tre” and the Icelandic word “þrír”. There are only so many ways in which morphology can stretch one and the same word root. Nevertheless, if we take inventory of what is available, then we can determine what is possible: There are three meanings of the word “buffalo” in English, referring to the animal, the city or the verb. That is why the following sentence reputedly makes sense: “Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo.”

With the technology of today, it seems perfectly viable (if mind-boggling) that any word, image or idea may be unraveled and expounded upon fully. And if we regard the artist’s creative output as a part of this grand project of mapping out all things, shouldn’t such a map have emerged some time ago? After all, according to Ernst Gombrich’s tradition, art history is at least 40,000 years old. Just a minor part of it, merely a few decades, was invested in the notion of artistic genius and originality. However, the bulk of the story is dedicated to the investigation, repetition, translation and appropriation of pre-existing objects, images or compositional patterns. Up to the present time, we do not seem to have run out of options, even though there have been numerous moments claiming that we have reached the end of art, come to art’s logical conclusion, or got stuck in a cycle of blank pastiche—to evoke but a few art-historical doomsday ideas.

However, there is a flaw in the idea of considering reality as a map, parts of which are still uncharted—even though some of us might feel like we are just about getting there. Theoretically, the concept might work if all artistic output was isolated immediately and put in the hands of appropriate authorities without anyone else noticing. We could then complete the task of mapping everything so that we might finally close this chapter and publish the mega-art-dictionary. One could imagine a concise metanarrative, based on a three-act structure: setup, conflict and resolution. Limited and fixed as this may appear, the combination of threefold variables in art still results in a cacophony of meanings. Art may preserve factual content but it is still conditioned by the artist’s subjective perspective. And the ensuing message, again, becomes conflicted on the receiving end where viewers attempt a translation of their own. Inextinguishable, artists continue to evoke new readings as they render the familiar strange and new again.

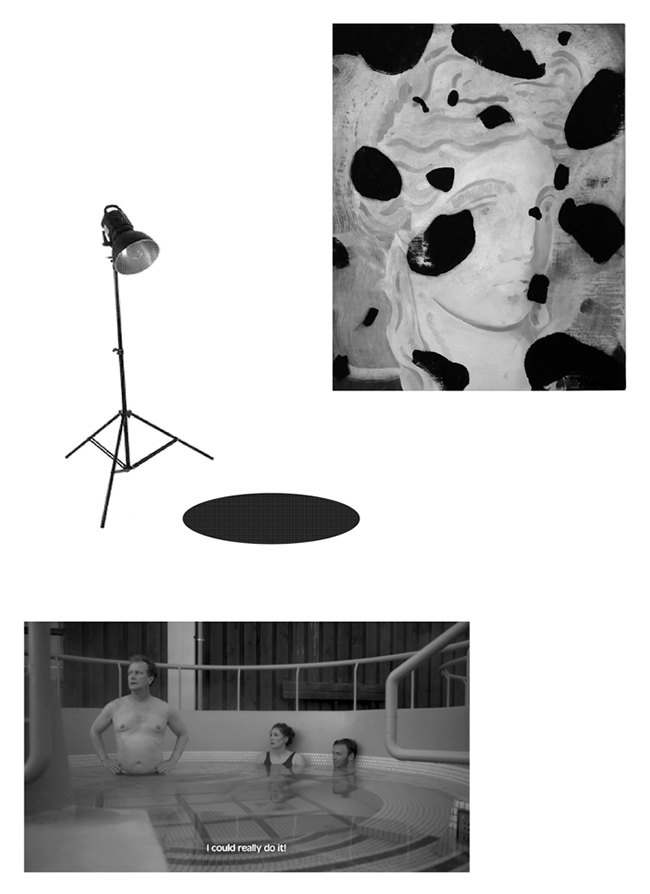

Emily Weiner employs a simple enough methodology, the creation of a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. One plus one becomes three in her juxtaposition of two images in one painting. Her work raises the question of what images want from us? Taking into consideration the power of images, the impact they have on our lives and the apparent urgency with which they demand a response from us, Weiner changes the power dynamics by switching from passive consumer to active and creative receiver. Her process reveals an inherent vulnerability behind the image. As she takes it in, lives with it and remolds it in her mind, she breaks its spell and makes it a part of her own vocabulary. Behind Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisathere is a simple triangle, the simplest of all polygons, that appeals to our subconscious desire for simplicity and completeness. Weiner brings the triangle forward, painting it in a pop yellow-pink gradient. Contrasting the massive shape, she alludes to the hands of Mona Lisa with gestural paint strokes at the front, while da Vinci’s Italian landscape with its two different perspectives appears in the background. The frame around the painting offers another layer; Painted in the same hues as the triangle, it simultaneously closes and limits the image field, while suggesting a bleeding out beyond the canvas.

Ragnheiður Gestsdóttir presents a composition of elements that each refer to familiar areas outside of art. She clutches at different kinds of research, theory or statements, on which the reality of our world and existence is predicated. These are then subtly manipulated and distorted by way of a commonplace DIY mentality. Not only does the work muddle up the subjects in question, but it also sheds a light on the issue of authority behind any stated truth. Thirdly, a new kind of statement emerges through the process, full of its own magic and enigma. By triangulating a square piece of paper, a dull two-dimensional shape, you are able to create an object that defies the laws of gravity and glides elegantly through the air. While the forces that allow a paper plane to fly are the same that apply to real airplanes, there are definite aerodynamic differences between a paper airplane and the Persian carpet that Gestsdóttir has folded to resemble one. Regardless, there are multiple historical sources behind the legend of the flying carpet. Merged together, these childhood preoccupations remind us of the value of contesting everything that is given, even if for no other reason than the thought experiment’s poetic value.

In Theresa Himmer’s video, three people appear together in a hot tub enjoying a moment of relaxation. They seem to know each other as their conversation dwells on the subject of mutual friends and neighbors. One of them gets the idea to swim home by traveling from one private swimming pool to the next, all the way to his house, and then sets out on the journey. Inspired by the American short story The Swimmer by John Cheever and its later filmatization from the sixties, Himmer changes setting, language and temporality, from the private villas of suburban America to present-day public pools in Iceland, while preserving the original names of all characters. The outcome is bewildering and humorous, reflecting the challenges involved in any kind of translation or localization. The work is in line with Himmer’s previous projects that muse on the subjects of memory, place and identity. She examines the changes that occur by taking a geographic, temporal or physical distance from architecture or other forms of cultural surroundings, and then attempting to revisit them.

Much as the relationship between the artist, her work and the viewer is a simple and uncompromising trinity, when further sets of three creep into the picture, as clearly seems to be the case in Speak Nearby, exponentiation raises the exhibition to the power of limitless possibilities. Celebrating this fact, the artist trinity leaves it to the viewer to decide if the latitude inspires despair or exuberance. There is as little chance that Gestsdóttir’s magic carpet will fly as the broken pottery in her photograph will reassemble itself. It is an impossible task to decipher all of Weiner’s multilayered images and morph them in one’s mind’s eye back to their original state (not all of them have Mona Lisa as an ancestor). The swimmer in Himmer’s film chooses a perfectly unreasonable way home, but against all odds it is the only way forward for him. It comes down to that: the way forward. Art succumbs to the same rationale as the law of physics, which is about entropy. Disorder always increases, never decreases. Increasing possibilities in the understanding of an image is in fact much more probable than the narrowing down of options, because artists continually choose from a large pool of deconstructed statements over a set of fixed and determined ones. And on these notes it is appropriate(d) to conclude with the fact that the number, three, is the computational ASCII-code for “End of Text.”

***

Ragnheiður Gestsdóttir is an artist heavily influenced by her background in visual anthropology, a field that deals critically with representation and the staging of culture and identity. Through film, sculpture, and installation, she explores the human desire for uniformity and absolute truths, while seeking to expose the impossibility of a true translation between different systems, languages, times, or places. Ragnheiður has exhibited at the Reykjavík Art Museum, The Living Art Museum, and Skaftfell Art Center in Iceland, Göteborgs Konsthall in Sweden, and Franklin Street Works in Connecticut, among other venues. Ragnheiður received an MA in Visual Anthropology from Goldsmiths College in 2001 and an MFA in Fine Arts from Bard College in 2012.

In her work, which includes photography, single-channel video, and installations in public space, Theresa Himmer uses architectural tropes, pop-cultural elements, and psychoanalytical references to reflect on aspects of place, locational identity, and memory. Through project-based research, she repeatedly seeks to address the various dynamics that produce both built and non-built spaces. Theresa is a 2012 graduate of the Whitney Museum Independent Study program, New York. She received her MFA in Fine Arts from The School of Visual Arts, New York, in 2011, and her M.Arch. from Aarhus School of Architecture, Denmark, in 2003. Group exhibitions include Nurture Art, Brooklyn; Young Artist’s Biennial, Bucharest; National Gallery of Iceland; and Westfälische Kunstverein in Münster, Germany. She has presented solo projects at Reykjavik Art Museum, Iceland, and Art in General, New York.

Emily Weiner is a painter living and working in Brooklyn. She is interested in how symbols move between the collective unconscious and individual perception. Her works juggle icons, geometries, and motifs which have been revived, reshaped, and recoded over time. Emily has exhibited work at harbor/Regina Rex, Sargent's Daughters, and Kravetz Wehby in New York; The Banff Centre in Alberta, Canada; Grizzly Grizzly in Philadelphia; and Camac Centre d’Art in Marnay-sur-seine, France. Emily received her BA from Barnard College, Columbia University, in 2003 and her MFA in Fine Arts at The School of Visual Arts in 2011.

Design: Arnar Freyr Guðmundsson

Text: Markús Thor Andresson

SOLOWAY

348 South 4th Street

Brooklyn NY 11211

contactsoloway@gmail.com

347.776.1023

Open Saturday and Sunday 12-5 and by appointment